Dose related growth response to Indomethacin in Gitelman syndrome

Lynster C T Liaw, Kaushik Banerjee, Malcolm G CoulthardDepartment of Pediatric Nephrology, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP, UK

Correspondence to: Dr Coulthard

Accepted 17 August 1999

Growth failure is a recognized feature of Gitelman syndrome, although it is not as frequent as in Bartter syndrome. Indomethacin is reported to improve growth in Bartter syndrome, but not in Gitelman syndrome, where magnesium supplements are recommended. This paper presents 3 sisters with Gitelman syndrome who could not tolerate magnesium supplements, and whose hypotension and Polyuria were eliminated by taking 2 mg/kg/day indomethacin, but who grew poorly. However, increasing the indomethacin dose to 4 mg/kg/day improved their growth significantly, without changing their symptoms or biochemistry. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage necessitated the use of misoprostol.

(Arch Dis Child 1999;81:508-510)

Keywords: Gitelman syndrome; Bartter syndrome; indomethacin; height; growth

Bartter and Gitelman syndromes are uncommon recessively inherited abnormalities of ion channels in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (Bartter), and the distal convoluted renal tubule (Gitelman),1 and they can present with a wide clinical spectrum. They share some features, including normotension in the presence of raised plasma renin activity and aldosterone concentrations, increased urinary potassium excretion causing a Hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, and Polyuria. Bartter syndrome is characterized by hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis, and may be associated with maternal polyhydramnios, premature birth and low birth weight, and early onset of symptoms, including vomiting, Polydipsia, dehydration with hypotension, muscle weakness, paresthesias, and developmental delay.2 3 In Gitelman syndrome there is hypomagnesaemia, Hypocalciuria, and no nephrocalcinosis, and many patients are asymptomatic, but may present with weakness and tetany, sometimes with abdominal pain, vomiting, and fever.3 4

Poor growth and short stature are seen in most children with Bartter syndrome,5-10 and a minority with Gitelman syndrome.9 11 Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors, particularly indomethacin, are used widely in children with disorders of the distal tubule because they may increase the proportion of glomerular filtrate that is absorbed in the proximal tubule, and thereby reduce symptoms of distal tubular impairment, such as polyuria. Indomethacin has also been reported to improve linear growth in Bartter syndrome,5-7 10 and appears to have prevented growth failure in one child treated from 1 day of age.12 Improved linear growth has been reported in one child with Bartter syndrome treated with growth hormone,8 and in one child with Gitelman syndrome treated with magnesium supplements.11 We report three sisters with Gitelman syndrome who were intolerant of magnesium supplements, and lost their hypotensive and polyuric symptoms when treated with indomethacin 2 mg/kg/day, but who were growing poorly. All three grew substantially better when the indomethacin was increased to approximately 4 mg/kg/day.

Case reports

This girl was born at term to unrelated parents, after an uncomplicated pregnancy, and presented at 0.4 years with failure to thrive. Investigations were characteristic of Gitelman syndrome, including very low plasma concentrations of potassium (2.3 mmol/litre) and magnesium (0.5 mmol/litre) in the face of a high fractional excretion into the urine (potassium, 49%; magnesium, 9.5%) and a high plasma bicarbonate concentration (27 mmol/litre). Her systolic blood pressure has been consistently normal in the presence of a raised aldosterone concentration (3720 pmol/litre at 0.42 years (upper limit of normal up to 1 year, 2929 pmol/litre13)) and persistently raised plasma renin activity (8015 ng angiotensin I/litre/hour at 0.42 years (upper limit of normal up to 1 year, 3130); 4200 at 3.3 years (upper limit aged 1-4 years, 2610); 1850 at 18.2 years (adult upper limit, 31113)). Her serum ionized calcium was normal (1.18 mmol/litre) but the urine calcium excretion (calcium to creatinine ratio, 0.1 mmol/mmol) was relatively low (mean (SD) in normal children aged 1-15 years, 0.40 (0.34)14), and a renal ultrasound excluded nephrocalcinosis.

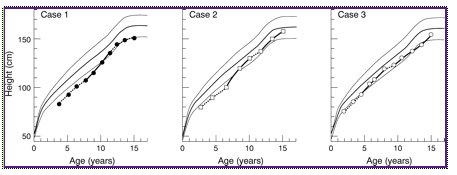

Indomethacin was started at 1 mg/kg/day in three divided doses together with potassium supplements (which have been needed ever since) until she was referred to our unit at age 4.8 years, when the indomethacin dose was increased to 2 mg/kg/day because she remained hypokalaemic. She then remained clinically well, with normal plasma bicarbonate concentrations, and potassium concentrations at the low end of the normal range. However, she grew poorly over the next four years, with a mean height velocity of 6.5 cm/year (fig 1). Because of this, the indomethacin dose was increased to 4 mg/kg/day at age 8.9 years, which resulted in a sharp increase in her height velocity (fig 1), with the height velocity standard deviation score reaching a peak of +3.4 (fig 2).

Figure 1 Growth of three sisters with Gitelman syndrome treated with indomethacin. Solid lines are periods of high dose treatment (4-5 mg/kg/day) and interrupted lines are periods of lower dose treatment (1-2 mg/kg/day). The third, 50th, and 97th height centiles are also shown.

She was started on misoprostol after one of her younger sisters developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding while also on high dose indomethacin. At 12.4 years, while taking indomethacin at 5 mg/kg/day, she suffered a large gastrointestinal bleed herself, despite remaining on misoprostol, and her indomethacin was then discontinued. Without indomethacin, she developed polyuria and polydipsia to the point of social embarrassment, and postural hypotension so severe that she was unable to stand up. However, these symptoms resolved immediately on re-introducing indomethacin at 1 mg/kg/day. Because her growth was almost complete by then, she has remained on this low dose ever since.

At 15.1 years, she was treated with oral magnesium supplements, increasing from 0.3 to 0.6 mmol/kg/day. Even at the lowest dose she developed diarrhea, and at the highest dose, her plasma magnesium failed to increase noticeably, she remained dependent on indomethacin to prevent hypotension and polyuria, and her diarrhea became intolerable, so treatment was stopped.

CASES 2 AND 3

These two girls were identified as having Gitelman syndrome on screening in the 1st week of life, with almost identical biochemistry to the first sister. Simultaneously with their older sister, they were initially treated with 1-2 mg/kg/day of indomethacin and potassium supplements, with similar biochemical benefit. They had their indomethacin dosages increased to approximately 4 mg/kg/day at the same time as the first sister, also for poor growth, when they were aged 6.5 and 4.6 years (fig 1), and subsequently showed dramatic increases in their height velocity standard deviation scores (fig 2).

When the oldest sister had her indomethacin temporarily stopped because of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and restarted at a lower dose, the other two also had their dosage reduced to 1-2.2 mg/kg/day. They also tried oral magnesium supplements at the same time as their older sister, but they too developed intolerable diarrhea without receiving any clinical or biochemical benefit. After 1.6 years on low dose indomethacin, they had again achieved poor height velocities (fig 1), so their doses were increased back up to 4 mg/kg/day. As before, this resulted in increased height velocities (fig 1) and standard deviation scores (fig 2). As with their older sister, the dose of indomethacin was reduced to 1 mg/kg/day once growth was complete. They remained clinically and biochemically well on this.

DiscussionMagnesium supplements have been described as being useful in Gitelman syndrome,11 15 but did not give any clinical or biochemical benefits in these three girls, in whom they had to be stopped because of intolerable diarrhea. Magnesium supplements have been shown to have no impact on intracellular or extracellular potassium concentrations in Gitelman syndrome.16

The exact mechanism whereby indomethacin improves linear growth in Bartter syndrome5-7 10 is uncertain, and there have been no reports correlating the increased height velocity with indomethacin dosage. In these three sisters, low dose indomethacin of 1 to 2 mg/kg/day controlled the clinical symptoms and improved the biochemical abnormalities caused by their Gitelman syndrome, but did not affect growth. However, they all showed a pronounced increase in linear growth velocity when the dose was increased to 4 mg/kg/day. This effect was similar at all the ages that they received it, ranging from 4.6 to 15 years.

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a well known side effect of prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors. The two sisters who suffered this did so only while on high dose indomethacin. Misoprostol, an orally active analogue of the naturally occurring prostaglandin E1, inhibits gastric acid secretion and has cytoprotective properties in the gastric mucosa, and has been used successfully for preventing gastric ulcers being induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.17 Although it was probably partially protective in these girls, one still had a brisk bleed while being treated with this drug.

It could be postulated that misoprostol might negate the positive effect of indomethacin, either on the renal tubule or on growth, because it is an analogue of prostaglandin E1, which might have had separate direct extra gastric effects. However, this was not the case; it remained effective in all three patients.

We recommend that children with Gitelman syndrome who are intolerant of magnesium supplements, or in whom these fail to control the clinical or biochemical abnormalities, are treated with indomethacin at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg/day. We suggest that if they grow poorly, the dose is increased to 4 mg/kg/day until they have completed their linear growth, and also take misoprostol while they remain on this higher dose. It might be that there is also a dose dependent effect of indomethacin on growth in Bartter syndrome, although this remains to be tested.

AcknowledgmentsWe are grateful for advice and help from Dr T Cheetham and E Avis.

Footnotes* ADC has adopted the Royal Pharmaceutical Society recommendation that journals use the recommended international non-proprietary name (rINN) for medicinal substances, following the recent European directive (92/27/EEC).

| 1. | Pearce SHS. Straightening out the renal tubule: advances in the molecular basis of the inherited tubulopathies. Q J Med 1998;91:5-12 . |

| 2. | Simon DB, Karet FE, Hamdan JM, Pietro AD, Sanjad SA, Lifton RP. Bartter's syndrome, hypokalaemic alkalosis with hypercalciuria, is caused by mutations in the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC2. Nat Genet 1996;13:183-188 [Medline] . |

| 3. | Rodriguez-Soriano J. Bartter and related syndromes: the puzzle is almost solved. Pediatr Nephrol 1998;12:315-327 [Medline] . |

| 4. | Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Bia MJ, et al. Gitelman's variant of Bartter's syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet 1996;12:24-30 [Medline] . |

| 5. | Littlewood JM, Lee MR, Meadow SR. Treatment of Bartter's syndrome in early childhood with prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors. Arch Dis Child 1978;53:43-48 [Abstract] . |

| 6. | Dillon MJ, Shah V, Mitchell MD. Bartter's syndrome: 10 cases in childhood. Q J Med 1979;48:429-446 [Medline] . |

| 7. | Proesmans W, Massa G, Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx M. Growth from birth to adulthood in a patient with the neonatal form of Bartter syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1988;2:205-209 [Medline] . |

| 8. | Regueira O, Rao J, Baliga R. Response to growth hormone in a child with Bartter's syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1991;5:671-672 [Medline] . |

| 9. | Bettinelli A, Bianchetti MG, Girardin E, et al. Use of calcium excretion values to distinguish two forms of primary renal tubular hypokalemic alkalosis: Bartter and Gitelman syndromes. J Pediatr 1992;120:38-43 [Medline] . |

| 10. | Seidel C, Reinalter S, Seyberth H-W, Scharer K. Pre-pubertal growth in the hyperprostaglandin E syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1995;9:723-728 [Medline] . |

| 11. | Taylor AJ, Dornan TL. Successful treatment of short stature and delayed puberty in congenital magnesium-losing kidney. Ann Clin Biochem 1993;30:494-498 [Medline] . |

| 12. | Mackie FE, Hodson EM, Roy LP, Knight JF. Neonatal Bartter syndrome |

| 13. | Dillon MJ, Ryness JM. Plasma renin activity and aldosterone concentration in children. BMJ 1975;4:316-319 [Medline] . |

| 14. | Ghazali S, Barratt TM. Urinary excretion of calcium and magnesium in children. Arch Dis Child 1974;49:97-101 [Medline] . |

| 15. | Bettinelli A, Metta MG, Perini A, Basilico E, Santeramo C. Long-term follow-up of a patient with Gitelman's syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1993;7:67-68 [Medline] . |

| 16. | Bettinelli A, Basilico E, Metta MG, Borella P, Jaeger P, Bianchetti MG. Magnesium supplementation in Gitelman syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 1999;13:311-314 [Medline] . |

| 17. | Graham DY, Agrawal NM, Roth SH. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastric ulcer with misoprostol: multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 1988;ii:1277-1280 . |